Pass the Cadmium Red, Honey by Robert G. Edelmanhttp://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/edelman/edelman5-29-03.asp

Pass the Cadmium Red, Honey

by Robert G. Edelman

I've always been somewhat in awe of artist couples. It's a wonder that they manage to keep personal ambition and mutual support in some kind of equilibrium. It's one thing to be a creative couple, say, a classical pianist and a novelist, or an architect and a dancer. But to work in the same medium with the same tools as your spouse, well, that takes a certain ego strength. Think of the daily challenges of a second opinion; i.e., "Sweetheart, I just looked at your painting, and honestly, I think you took a wrong turn somewhere last night after I went to bed."

This stormy spring has brought New York a great pair of exhibitions on this very topic. "Out of the Shadows: Helen Torr, a Retrospective" at James Graham Gallery surveys the work of the spouse and soul mate of that pioneer of American abstraction, Arthur Dove. At the same time, Knoedler & Co. has mounted "Sally Michel/Milton Avery, A Portrait," a special exhibition of images of each other made by the celebrated artist couple.

Helen Torr (known as "Reds" for her flaming tresses) was, as the Graham show amply demonstrates, a painter of skill and distinction. That she managed to produce work of quality while being all but marginalized by the modernists of the Stieglitz group is even more impressive, considering how much importance she placed in their approbation. After all, Dove has always been considered one of the torchbearers of abstract painting in America, an artist who made the break from representation and assimilated European influences (simultaneously with Kandinsky, in 1911-12) before any of his compatriots. As singular and innovative as Dove's work proved to be, Torr developed a touch and sense of color that is all her own. It permeates her work, regardless of how much she borrowed stylistically from others.

Not that Torr had anything but an ally in her husband. He was her champion and supporter, in fact, throughout all their years together. According to Anne Cohen DePietro's informative catalogue essay, Dove attempted to get Stieglitz and other modernists to pay attention to her work, though with only limited success. In 1933 Torr and Dove had a two-person show at Stieglitz's gallery, An American Place, and Dove would send missives from time to time updating Stieglitz on her progress.

"Reds is working too," he wrote, "is finding some things -- Color very clean and clear." Georgia O'Keeffe, who had her own struggle to survive within the competitive Stieglitz orbit (despite the obvious advantage of her personal connection to the maestro), may have been disinclined to lend her support to Torr's work, insecure in her own role as den mother. Torr seemed to accept all this quietly (she kept a journal), as though it might have been the inevitable order of things.

These difficulties didn't, however, stop her from painting. To keep working, she battled physical ailments, periods of non-productivity and cramped quarters on their sailboat, the Mona, as well as a commitment to the year-end selection and framing of Dove's work for his annual exhibitions.

As a painter, Torr was aware of the experimentation and innovations of her contemporaries and borrowed freely from them, a way of using what she could to further her own vision. In fact, she worked through these influences only to come to the conclusion that her strength lay in a direct response to nature and her environment, something she ultimately developed through careful observation and an imaginative approach to form. In those heady days of the infancy of American Modernism, the exchange of ideas was crucial to the development of a national artistic identity, generating experimentation that required a sharing of methodology.

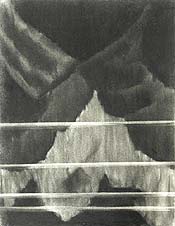

Part of the pleasure of the exhibition at Graham is studying the influences of other artists on Torr's efforts. Her attentive variations on Dove's work, which are often her most abstract pictures, have an austere, dark beauty, as in the charcoal drawing Geometric or the richly tonal Hill Forms, and the small oil study, Mountain Mood, ca. 1923-24.

Torr found inspiration in Georgia O'Keeffe's voluptuous forms and saturated color, in her Abstract Flowers (1926), and references O'Keeffe's New Mexico paintings with her own White Cloud (Light House) of 1932. The organic compositions of Marsden Hartley, the structural clarity of works by Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, the brooding landscapes of Charles Burchfield, can all be felt in Torr's art.

Yet, works such as Melodrama (1931) and Hecksher Park (1932) though illustrational in feeling, are paintings that reveal the artist's nature and temperament, first and foremost. Torr's inventive abstractions from the late '30s, such as From Piano (Music Painting) and Autumn Forms, do not appear to reference anyone else's work, including Dove's.

As Dove's health deteriorated in the early 1940s, Torr gave up her painting to care for her ailing husband. When Dove had a stroke and suffered a partial paralysis, Torr helped him execute his last series of paintings. After Dove's death, Torr stayed in their single-room house in Centerport, L.I., for the rest her life, stored her work in the attic, and created delicate, handmade cards for friends.

One thinks of Lee Krasner, who was able to thrive as an artist, doing her best work after Jackson Pollock's death. Torr's creative life was profoundly tied to that of her husband's, and her great regret was that Dove did not live to see his work achieve wider recognition. But their respect for one another as artists can be summed up in one of Dove's journal entries: "Reds did leaf in new technique -- swell."

In Milton with Wild Hair, Avery's massive head fills the small canvas. A bold palette of orange with various shades of green and violet animates the artist and his unruly mane. Seeing Michel's pictures opposite Avery's demonstrates that this was a couple inspired by the ongoing correspondence in their work. That the Averys also shared a painter's commitment to bold color, deceptively simple composition and an abiding love of nature is evident in their work from over 40 years of cohabitation.

Michel and Torr were woman artists who had the mixed blessing of being aligned with husbands who were major contributors to American art. It should be clear to those who view both exhibitions, however, that these women were significant and accomplished artists in their own right, regardless of the time that it has taken for that truth to be acknowledged.

"Out of the Shadows: Helen Torr, a Retrospective," Apr. 24-June 8, 2003, at James Graham & Sons, 1014 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10021

"Sally Michel/Milton Avery, A Portrait," Apr. 24-May 30, 2003, at Knoedler & Co., 19 East 70th Street, New York, N.Y. 10021

ROBERT G. EDELMAN is an artist and gallery director of Anita Friedman Fine Arts.

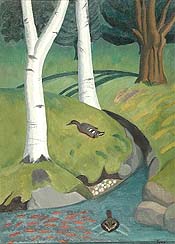

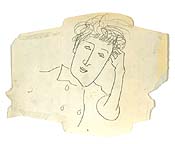

Helen Torr

Grazing Horses, Green Clouds

at James Graham & Sons

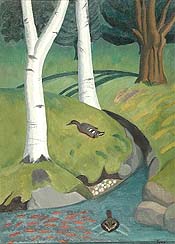

Heckscher Park

1932

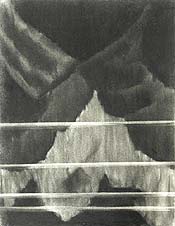

Shell, Stone, Feather and Bark

1931

Autumn Forms

Hill Forms

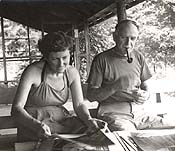

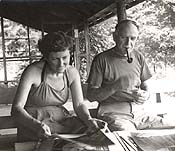

At Knoedler & Co., Sally Michel and Milton Avery, 1950

Sally Michel

Milton Thinking

ca. 1950

at Knoedler & Co.

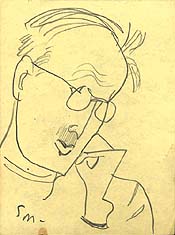

Milton Avery

Smiling Sally

1953

Milton Avery

The Artist and his Wife

1928

Grazing Horses, Green Clouds

at James Graham & Sons

Heckscher Park

1932

Shell, Stone, Feather and Bark

1931

Autumn Forms

Hill Forms

At Knoedler & Co., Sally Michel and Milton Avery, 1950

Sally Michel

Milton Thinking

ca. 1950

at Knoedler & Co.

Milton Avery

Smiling Sally

1953

Milton Avery

The Artist and his Wife

1928

No comments:

Post a Comment